CTF Writeup - UIUCTF 2020 - RFCland

20 Jul 2020

Tags:

ctf

forensics

file formats

protocol analysis

Introduction

CTF challenges in the forensics category usually deal with several kinds of data representations, from file formats to memory dumps. On this writeup, the goal was to extract the flag from a network capture in the pcap format.

Description

All RFCs are created equal, right?

Analysis

When opening the task’s pcap with wireshark, we see TCP traffic composed of several conversations. Each conversation is delimited by the 3-way handshake for establishing a connection:

TCP A TCP B

1. CLOSED LISTEN

2. SYN-SENT --> <SEQ=100><CTL=SYN> --> SYN-RECEIVED

3. ESTABLISHED <-- <SEQ=300><ACK=101><CTL=SYN,ACK> <-- SYN-RECEIVED

4. ESTABLISHED --> <SEQ=101><ACK=301><CTL=ACK> --> ESTABLISHED

5. ESTABLISHED --> <SEQ=101><ACK=301><CTL=ACK><DATA> --> ESTABLISHED

Followed by the connection close:

TCP A TCP B

1. ESTABLISHED ESTABLISHED

2. (Close)

FIN-WAIT-1 --> <SEQ=100><ACK=300><CTL=FIN,ACK> --> CLOSE-WAIT

3. FIN-WAIT-2 <-- <SEQ=300><ACK=101><CTL=ACK> <-- CLOSE-WAIT

4. (Close)

TIME-WAIT <-- <SEQ=300><ACK=101><CTL=FIN,ACK> <-- LAST-ACK

5. TIME-WAIT --> <SEQ=101><ACK=301><CTL=ACK> --> CLOSED

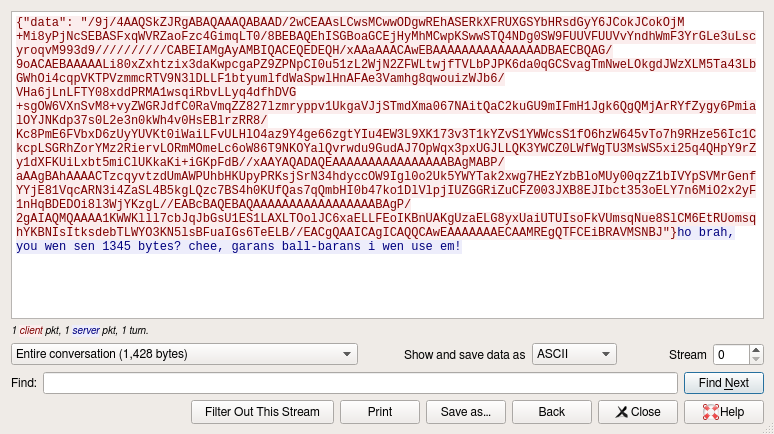

A condensed view for these conversations is selecting Context Menu > Follow > TCP Stream, where we quickly see the contents at play:

- From “10.136.127.157” to “10.136.108.29”: data transmission in json format, containg key “data” and a base64 value;

- From “10.136.108.29” to “10.136.127.157”: response string, containing the length of the received base64 value.

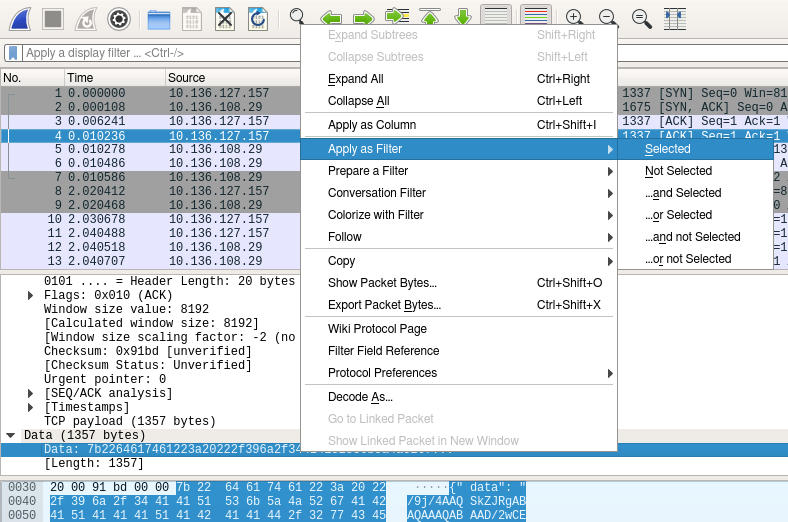

One way to parse these contents is to identify filters for the corresponding packets, which can be obtained by selecting a field in the details pane and selecting Context Menu > Apply as Filter > Selected:

Extract the data transmission packets:

tshark \

-r challenge.pcap \

-Y 'data.data && ip.dst_host == 10.136.108.29' \

-T json \

> challenge.json

Parse contents, decode base64 and dump the decoded data to files:

from ipdb import launch_ipdb_on_exception

import base64

import binascii

import json

import os

import sys

with open(sys.argv[1], "r") as f:

contents = f.read()

out_dir = './out'

if not os.path.exists(out_dir):

os.makedirs(out_dir)

with launch_ipdb_on_exception():

packets = json.loads(contents)

for i, packet in enumerate(packets):

if "data" not in packet["_source"]["layers"]:

continue

data = packet['_source']['layers']['data']['data.data'].replace(':', '')

hex_bytes_clean = ''.join(data.split())

raw_bytes = binascii.a2b_hex(hex_bytes_clean)

parsed_data = json.loads(raw_bytes)['data']

is_decoded = False

while not is_decoded:

try:

decoded_data = base64.b64decode(parsed_data)

is_decoded = True

except binascii.Error:

parsed_data += '0'

raw_bytes = decoded_data

with open("{}/{:08d}".format(out_dir, i), 'wb') as f:

f.write(raw_bytes)

Notice how some base64 values seemed to be truncated, so I had to add some padding bytes (parsed_data += '0') in order to decode them.

I’ve looked at response messages as well, by counting each distinct type of message (the only variable in the template is the received length, which is filtered out):

tshark \

-r challenge.pcap \

-Y 'data.data && ip.dst_host == 10.136.127.157' \

-T fields \

-e data.data \

| sed 's/://g' \

| xargs -i sh -c 'echo "$1" | xxd -r -p; printf "\n"' _ {} \

| sed 's/[0-9]\+\( bytes\)/_\1/g' \

| sort \

| uniq -c

Output:

66 cookies? nom nom nom, thanks for sending _ bytes

84 ho brah, you wen sen _ bytes? chee, garans ball-barans i wen use em!

86 Oh, is that all? Well, we'll just.. WAIT, WHAT?! You only sent _ bytes?

78 OwO what's this? _ bytes? wow, thanks, they wewe vewy yummy :)

Sure enough, one type complains about the number of received bytes. So maybe our data was being partially sent in some transmissions?

If we check the mime types of our data files:

file -k * \

| sed 's/[^:]*:[ \t]*\(.*\)/\1/' \

| sort \

| uniq -c \

| sort -n

We see several false positives, a few JPEGs, and unidentified files:

1 MPEG ADTS, layer II, v1, 64 kbps, 44.1 kHz, Stereo\012- data

1 Non-ISO extended-ASCII text, with CR, NEL line terminators, with escape sequences\012- data

1 Non-ISO extended-ASCII text, with no line terminators\012- data

1 PGP Secret Sub-key (v1) [...]

1 SysEx File -\012- data

1 TeX font metric data [...]

1 TTComp archive, binary, 4K dictionary\012- data

5 COM executable for DOS\012- data

51 JPEG image data, JFIF standard 1.01, aspect ratio, density 1x1, segment length 16, progressive, precision 8, 200x200, frames 3\012- data

251 data

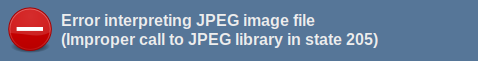

However, when attempting to open one of the images, our image viewer may spit out an unhelpful error:

But if we load one of the images in Kaitai IDE, it seems to be parsed successfully:

It appears that the file is truncated, with the last field corresponding to image data. I tried a more fault-tolerant approach by using imagemagick to convert these partial JPEGs to PNGs, which allowed me to view them:

file -k * \

| grep image \

| cut -d':' -f1 \

| xargs -i convert {} {}.png

Here are some of them:

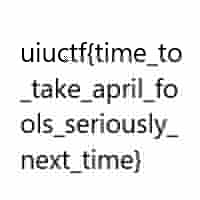

As we can see, they all seem blurry and corrupted, and notably one of them contains the flag! If we check the metadata with exiftool, we can see the encoding process is “progressive”. If you were fortunate enough to have enjoyed dial-up speeds in the past, the effect we see in our images corresponds to partially loaded image data, which could be observed with slower download speeds. For images encoded as “baseline”, you only got to see a few lines as it was being loaded.

With these insights, I went for a bruteforce approach, simply concatenating the non-image files (filtered by grep -v image) with the flag file, and inspecting them one by one to see if the image would get progressively more complete:

file -k * \

| grep -v image \

| cut -d':' -f1 \

| xargs -i sh -c 'cat 00000095 "$1" > ../out_2/"00000095_$1"' _ {}

With this process, we find that files 95 and 106 are a match. Concatenate these two and repeat the process. With the second iteration, we find that files 95, 106 and 223 give us the full flag:

Intended Solution

After the challenge ended, one of the organizers clarified what RFC they were referencing:

https://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc3514.txt you can analyze the packets to see some have the evil bit, the image data of those packets gives the flag

I tried to come up with an approach that would make this kind of “needle in a haystack” metadata more explicit. Given that only a few packets would contain the flag pieces, we wanted to observe metadata field values were most of the packets had one value and a few had another value (fields where all packets differed or were identical could be safely discarded).

Sticking with the line-oriented analysis, I flatten the tshark json output using gron, which allows us to aggregate each field across conversations, since the full path and value of a given field is output in a single line. The following awk script parses these lines by:

- Filtering out the initial prefix, which is just the index of the array of conversations;

- Counting each occurrence of a field value;

- Filtering out occurrences that only had one match (i.e. they were distinct in all packets);

- Printing the occurrence count and the value for each field, sorted at the end for manual comparisons.

gron challenge.json \

| awk '

match($0, /^json\[[0-9]*\]\./) {

s = substr($0, RLENGTH + 1, length($0))

a[s]++

}

END {

for (i in a) {

if (a[i] != 1) {

print a[i] " " i

} } }' \

| sort -n

In a first pass, fields related to time deltas and lengths can be ignored, as these are less likely to contain relevant information. We can also ignore those that match the total number of conversations (314). Eventually we find some mostly common fields (309), related to flags in the IP protocol:

[...]

9 _source.layers.tcp["tcp.analysis"]["tcp.analysis.bytes_in_flight"] = "1314";

9 _source.layers.tcp["tcp.analysis"]["tcp.analysis.push_bytes_sent"] = "1314";

9 _source.layers.tcp["tcp.len"] = "1314";

9 _source.layers.tcp["tcp.nxtseq"] = "1315";

309 _source.layers.ip["ip.flags"] = "0x00000000";

309 _source.layers.ip["ip.flags_tree"]["ip.flags.rb"] = "0";

314 _index = "packets-2020-07-18";

314 _score = null;

314 _source = {};

314 _source.layers = {};

[...]

Seems like ip.flags.rb is a good candidate for closer inspection. If we look at the other values for this field:

[...]

5 _source.layers.ip["ip.checksum"] = "0x000074cb";

5 _source.layers.ip["ip.checksum"] = "0x000074d2";

5 _source.layers.ip["ip.checksum"] = "0x000074d9";

5 _source.layers.ip["ip.flags"] = "0x00008000";

5 _source.layers.ip["ip.flags_tree"]["ip.flags.rb"] = "1";

5 _source.layers.ip["ip.len"] = "1364";

5 _source.layers.ip["ip.len"] = "1368";

5 _source.layers.ip["ip.len"] = "1371";

[...]

We find that a few had the reserved bit set. It seems to match the description for the “evil bit” in the RFC:

The high-order bit of the IP fragment offset field is the only unused bit in the IP header.

Now we can repeat the data extraction process, this time with a finer-grained filter:

tshark \

-r challenge.pcap \

-Y 'data.data && ip.dst_host == 10.136.108.29 && ip.flags.rb == 1' \

-T json \

> challenge_rb_set.json

./challenge.py challenge_rb_set.json

cd ./out

file -k *

There is only one image file and a few unidentified files:

00000000: JPEG image data, JFIF standard 1.01, aspect ratio, density 1x1, segment length 16, progressive, precision 8, 200x200, frames 3\012- data

00000001: data

00000002: data

00000003: data

00000004: data

The flag can be obtained by concatenating the first 3 files, although I still required the convert workaround to view it.

To figure out why the image was considered invalid, I looked up a breakdown of the JFIF file format, which lead me to search our files for the “end of image” marker with grep $'\xff\xd9' *, which returned no matches. So the complete flag also needs those magic bytes appended to work with picky image viewers:

cat 00000000 00000001 00000002 <(printf '%s' $'\xff\xd9') > flag.jpg